Alfred Elton van Vogt (1912-2000)

|

|

A.E., »The Van who sold the future« (Forrest J Ackerman, sein Agent, in typischer ackermännischer Verballhornung eines Heinlein-Titels) hatte einige Brüder, Ed, Ira und Arthur. Ob sie bzw. welche davon noch leben, weiss ich nicht. Er war zweimal verheiratet, und seine erste Frau, Edna Mayne (er sprach von ihr als Mayne) schrieb auch SF, und manchmal mit ihm zusammen. (»I always had to put my special brand of adjectives in her texts«, sagte er mir einmal).

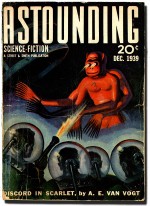

Seine erste SF Story war »Black Destroyer«, 13.000 Worte, im Juli 1939 in »Astounding«, gefolgt von »Discord in Scarlet« (Dez. ’39), „Repetition“ (April ’40) und dann „Vault of the Beast“ (August ’40). Dann kam „Slan“ (in Fortsetzungen, Sept.-Dez. ’40), alle in „Astounding“, und danach noch viele mehr, bis „The Wizard of Linn“ (April-Juni ’50). Fantasy erschien von ihm mehrmals in „Unknown Worlds“, zuerst „The Sea Thing“ (Jan. ’40). Van Vogt war einer von ganz Wenigen in den USA (Heinlein schätzte sie auf nicht mehr als 500), die ihr Leben ausschließlich mit dem Schreiben von Fiction fristeten.

Jeder Nachruf auf ihn wäre freilich unvollständig, wenn er nicht sein unersättliches Interesse an wissenschaftlichen Dingen überhaupt und seine Wissbegier daran erwähnt. Alles faszinierte ihn: Mathematik („Vault of the Beast“ handelt von Primzahlen), Kosmologie und Relativitätstheorie, Physik, Genetik, alle Lebensphasen von der Geburt bis zur Geriatrik und Un/Sterblichkeit, später dann vor allem mentale/spirituelle Grenzgebiete.

Er sah Heil und Wachstum für die Menschheit in mentalen Theorien, aber um dorthin zu kommen, hat er sich jahrelang intensiv, aber völlig autodidaktisch, mit dem menschlichen Phänomen überhaupt beschäftigt. Er war der klassische Autodidakt, hochintelligent aber sich dabei seiner mangelnden Schul- und Hochschulbildung schmerzlich bewusst. Die kreative Fähigkeit seines Gehirns war ganz ungewöhnlich hoch, und da er sich ständig selbstanalysierte, immer sehr objektiv und ehrlich, oft schonungslos, war er überzeugt davon, dass SF bei der Jugend schlummernde Kreativität erweckt, die sonst u.U. verkümmert. Darin sah er später auch sein Raison d’Etre.

Besonders faszinierte ihn das Phänomen Mann und/kontra Frau. Einer seiner besten nicht-SF-Bücher ist der Roman „The Violent Man“ (1962), eine packende Studie über Rotchina, Gehirnwäsche und die Verbindung zwischen Gewalt und Machismo – also männliches Gehabe. Er arbeitete auch an einem Werk über die Frau – was daraus geworden ist, weiss ich allerdings nicht. Irgendwie betrachtete er Frauen immer als sehr merkwürdige, unerklärliche Wesen, als ob er seltsame Schmetterlinge von einer anderen Welt vor sich hatte. (Einmal sagte er mir, die Aufgabe einer Frau sei es, einfach schön zu sein, und er nahm Zsa Zsa Gabor als Beispiel der „typischen Frau“). Als ein Mensch, der eine bettelarme Jugend verbracht hatte, faszinierte ihn auch das Phänomen Geld und der Menschentyp, dem es „zufliesst“, und auch daraus entstand ein interessantes nicht-SF-Buch voll soliden aber auch bizarren Quasi-Theorien, „The Money Personality“ (1972), und aus seinem Interesse an allem Mentalen entstand 1956 das akribisch detaillierte „Hypnotism Handbook“ (mit C.E. Cooke) für den autodidaktischen „Selbstunterricht“.

Ja, er war ein ganz besonderer Mensch, mit einem Gehirn, das auf ungewöhnlichen Wegen dachte und andere Gehirne »twisten« konnte. An sich war er für mich auch eine sehr tragische Figur: Als ein Mensch mit einer derartigen Intelligenz und Kreativität hätte er es unendlich weit bringen können, wenn er eine ordentliche Schulbildung und ein akademisches Studium gehabt hätte. Und er wusste das, und das Bewusstsein kam immer wieder in dem, was er sagte, zum Vorschein und gab ihm eine innere, den Mitfühlenden anrührende Melancholie. Die Wirtschaftskrise der 30er Jahre und Armut seiner Eltern, die Jugend auf einer kleinen Farm in Kanada, boten keine Chancen. Und doch hat er nicht zugelassen, dass sein Gehirn verkümmerte: er hat das Beste, was er machen konnte, aus sich gemacht, und hat sich auf seinem Lieblingsgebiet, wie die Anteilnahme der westlichen Welt an seinem Sterben zeigt, die Unsterblichkeit erschrieben.

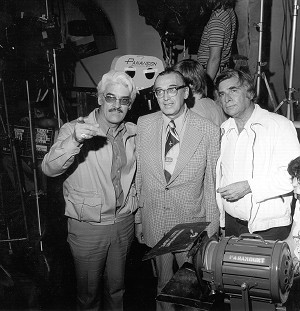

This photo was taken back in 1978 on the set of »Star Trek – The Motion Picture« (Robert Wise, dir.) at Paramount (in fact behind the »Enterprise« Bridge construction), when I spent a little vacation leave from NASA with Gene Roddenberry to assist him as Technical Advisor on the picture. One day, we invited my old friend A.E. to the set, and the event turned into a meeting of the mutual admirer’s club. Gene had read a lot of A.E.’s writings when flying as a TWA airline pilot on long intercontinental hauls, and particularly A.E.’s »Voyage of the Space Beagle« helped Gene to conceive of Star Trek.

|

|

I asked Van Vogt during that visit to Paramount whether he wouldn’t like to see his own books turned into movies, and I remember him replying that he felt that his style was just not suitable for the screen: the imaginative power of his writings spoke to the cerebral sense much more than to the visual (as opposed to what Gene did with Star Trek – pure video). What went on in Gilbert Gosseyn’s mind or in the strange mind of Coeurl („On and on Coeurl prowled.“, one of the most famous openings of an SF novel of all time…with five words, he hooked you right then and there ) couldn’t be brought to the screen, but it was why one read his stuff in the first place. A.E.’s was truly „literary“ SF which absorbed (and then twisted) the mind. Of course, however, there also was the acknowledged fact that Ixtl from „Voyage of the Space Beagle“ (originally „Discord in Scarlet“) was the model for the alien in „Alien“.

As I mentioned in the tribute, I translated most of his booklength mind-twisters („Voyage“, „Slan“, „Mixed Men“, „Null-A“, et al.) and countless short stories into German during the 50’s, and I always had great, great fun doing it. His „wheels within wheels within wheels“-style wasn’t easy to translate (he didn’t write „linear“ but in strange curves and jumps and changing levels of consciousness, with subplots and other intricacies, while always returning to the main thread and tying up loose ends) but absorbing, and I always tried to somehow „mirror“ his style in the German language. It also affected my own SF writings during my student years, and one of my books, „Die Reise des Schlafenden Gottes“ (The Voyage of the Sleeping God) was deliberately „van-Vogt-ish“, a take-off which tried to pay tribute to the Master by somehow emulating him.

Well – that was back then, before the real space program got a hold of me… But there is no doubt whatsoever that a lot of folks in NASA were originally turned on by classical „literary“ science fiction to go after higher education in order to make their careers in the space program, and A.E. van Vogt was among the first and the best who gave their imagination the wings to travel lightyears.

I guess you are aware of the little autobiography A.E. wrote and published. There’s good material in there.

© Prof. Dr. Jesco von Puttkamer (Text und Bildmaterial)